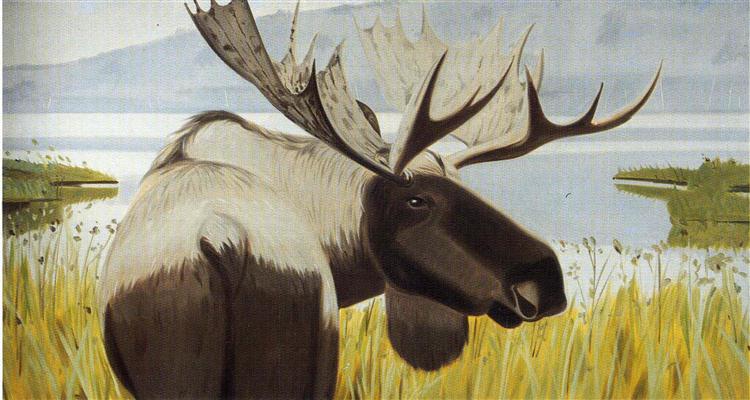

Katz, Alex. Moosehorn State Park.

LILACS by Nicole Treska

I remember dark nights and country roads with no lights and steep drops and our daddy saying that in the case of a moose in the road, the thing to do was hit it hard. Everyone swerved, he said; a foolish instinct to save a stupid animal. You swerve and you hit tree, or you drive off a cliff. You see a moose, you speed up and hope to knock it clean out the way. Thing is, with legs that high a moose is liable to drop right on top of you. A moose in the road means trouble is already upon you. Someone’s getting hurt, only question is who.

The day the moose turned up we were bored—like hurt yourself bored—and had decided to throw my little sister to the pigs. It was the late afternoon of a late summer day, so somehow all of my days in Maine: tall grass, ticks and flies, and lilac—purple and white on the wind, in bloom one day and wilted the next.

That year I was seven and Billy the neighbor, she was nine. She wore a back brace made of hard plastic that squeezed her tight and kept her spine from sagging. Her mother called it an accident of nature, said there wasn’t anything anyone could do about it. Billy’s brace screwed into a metal frame that grew into a chin rest, which by design thrust her gaze slightly skyward. Her shoulders sloped and when she ran it kind of looked like she was skipping. The effect was unfortunate, but Billy walked around like farm royalty squeezed into some kind of rarified country corset. Sometimes, when she asked, I would turn the ridged metal knobs that punctuated her plastic back like a spine—loosen the brace a little, so she could breathe.

Billy was what my mother would call a real Mainah, the meaning of which I could never quite gather, save that it was not the most flattering thing my mother could say about you. I liked Billy fine. She was country, but there was something upright in the way she carried herself that had nothing to do with the brace. Like she knew something. Plus she lived next door, and that made us friends. Our sisters were small, dirty, and younger than us, thus well suited to one another.

We played hide and seek in the yard that attached our properties: large enough for hills to roll and trees to stand in thatches, for the chicken coop that was theirs and the storage barn that was ours and filled with the dulled blades of farm equipment—tired out, but blades nevertheless.

In the barn, the old cat killed mice and dragged them into the hollow walls to tear their guts out. She was a ferocious thing and our presence bothered her not at all. She would trot past where we were folded between scythes and rotors, a head pinched in the side of her mouth, without so much as a sidelong glance. She worked tirelessly, the way everyone on a farm works, and was not one for chit-chat. It smelled of rotting rodents and wet hay in there, and it was where we did our best hiding.

Our daddy was rebuilding an old Ford when he felt like it and the car sat on blocks in the middle of the barn. The engine hung from the hoist like a heart on a chain, and the scent of thick motor oil almost masked the scent of dead mouse.

“I’ll count to twenty, then I’m coming for you,” Billy said. She had a thick accent, so she said it like, comin’ fo-ah yuh.

We scattered while she counted and the old cat ran low. Billy was easy enough to hear coming. Her brace lent her gait a certain squeak and lurch. When she yelled, “Ready or not, here I come!” no one really felt afraid. Hea-uh, she said.

Back behind the house and the pastures, the wood rose to surround everything. Spruce and pine so green it looked black in places, the forest reached out in either direction to meet the road and gave off a low and constant hum.

We weren’t allowed to go where the big trees stood. Our mother said in woods that big there was danger that big, too. When we asked her to clarify, she told us that one day we would understand.

Our mother picked blackberries from the bramble that grew around the trunks of the tree line and often came home with her hands covered in stinging little scratches, her fingers stained from having squeezed too hard and popped the drupelets.

We saw her in the driveway, basket of berries at her side, squinting down at our Grandpa, who rooted around in the pigpen—a sunken enclosure where the sows and piglets were rarely quiet. From that distance we couldn’t see her face; the heat wobbled around and a Maine day’s worth of pollen and mosquitoes spun in the air. She was all blurry softness, the way mothers should be. And even though her voice sounded terse we ran to her with the unrestrained speed of kids who hadn’t fallen enough to know any better. Billy brought up the rear.

“Frank, the girls are coming, couldn’t you do this later?” Our mother would not go so far as to call her relationship with our daddy’s daddy all sunshine and rainbows.

“Dead pig! Incoming!” came our grandpa’s reply from down the hole. He flung a dead piglet up over the edge of the pen, and it landed, small and mud-crusted, stiff and sudden, in the grass.

The piglets were not so small we could hold them in our hands anymore. Now they ran in little packs, squealing and delighting in games and mud baths with their tails coiled exactly the way you’d think. We got on capitally.

“Don’t be afraid,” our mother said as we neared the white piglet that had been pink when last we’d seen it, and part of life.

“Why shouldn’t we be afraid?” Billy’s sister said in that way of hers that sounded either sage or stupid, depending who you talked to.

“It was an accident,” our mother said. “Grandpa said the mama crushed the baby.” She was pregnant then. My youngest sister took on my mother’s worry in the womb.

Our grandpa hitched himself up the ladder and out of the pen. He walked with a short and insolent step, dragging his war-stiff leg behind him. His flannel shirt was rolled to the elbow and he held the rake out away from his body. His boots, and his boots only, were covered in thin mud. He stopped before us and scratched at the sharp black and white scruff that grew down his neck.

“See what happens when you don’t get outta your own way?” He picked up the baby pig by the back leg. “Take a good look.” He gave the dead baby a shake and laughed a laugh that did not sound happy. “Watch your ma’ don’t sit on you next. A pregnant sow gets on you, and, well…”

My mother said, “Frank, please.”

He shrugged and walked off behind the house, pig swinging at his side like a lunch pail. The afternoon carried on showing no sign of sadness, and the sun dropped toward the tree line. Grandpa used the rake to pull himself up the hill and into the heavy wood.

As grandpas went, ours was not of the butterscotch variety. He did not slip a tenner in your pocket. He had better things to do with a knife than whittle. His was a high sour smell, and every room our grandpa lived in and every shirt he owned smelled of his toil. He wasn’t sure of our names, so he avoided most direct address, speaking to no one and everyone all at once.

“He never really loved your daddy. Remember that. He’s a brave man, but he’s cold,” our mother said. “Blaming your daddy because his daddy didn’t hug him enough, that won’t do any good. And Grandpa went to war. And his parents had their worries. And their parents, and theirs, and on and on. No real use in blaming.”

She looked toward a remote place ahead of her like she was trying to put something together. Billy stood in our mother’s round shadow, with the kind of adoration on her face everyone just knows isn’t mutual.

Our mother fancied the domestic past-times of Maine, and took to basket weaving and berry picking with studied attention. She was sure that if she became the housewife that pickled and jarred and quilted that she could seal up the life she wasn’t given. Save it for leaner times, hold it in her hands and count it.

She used to sew in a small room on the third floor of the farmhouse. She made our clothes up there, and once we were outfitted in smocks and blouses, she switched to quilts.

The needles punched through fabric and stuffing with such a force that the thin floors trembled right down to the ground. Quilting needles are thick. She was running off an edge one day when her thumb slipped, and quick as that the needle punctured her nail and the soft flesh underneath, her thumb impaled and bloodless on the bobbin plate. It was not the pain that made her put the machine away for good, but the ease, the swiftness with which something bad had happened. She brandished her sunken thumb as a cautionary tale, looking hard at her little daughters, and waiting for us to understand what kind of a world we lived in.

I remember the quilt—a spiral of black fabric with tiny bunches of purple and white lilacs, like the ones in the yard.

We watched her walk off across the grass grown long enough to sway against her legs. The mottled old cat slept somewhere out of sight and Grandpa had not emerged from the woods. We were alone again.

“We’re about bored to death.” My sister said, her fists raised in an approximation of adult dissatisfaction. She had one of those potbellies like a starving kid, and dried snot that stained her face from nose to ear. Her knocked knees spoke of legs to come, and she got growing pains so bad she cried in the night for our mother to rub her achy bones.

She wiped the back of her wrist across her face and pointed into the pen. “You think there’s another dead baby down there?”

“Someone should check,” I said, knowing full well my Grandpa would never, but going ahead because I could see by my sister’s face she would let me.

“Youngest first,” I said, and the other two nodded in vigorous agreement, happy the task had not arbitrarily fallen to them. The pigs only acknowledged us marginally, far more interested in rooting and bumping through the muck for the cores of things we didn’t finish, the fibrous things we couldn’t digest. They were always decorous, those pigs, and they never knocked us over. We had no reason to be afraid of them, but still. But still.

My sister whimpered a little on the ladder, but kept on anyway, fingers and toes slippy on the rungs. Below her the pigs rolled in smooth circles, staying cool and tickless to spite everything. They waved their snouts and hooves skyward and were entirely without malice, but we were learning that malice had very little to do with anything.

We watched my sister with the newfound fear that something bad could happen. We could feel it in our throats, somewhere above our guts, not quite made it to our mouths.

Just then the truck rounded the corner. Our daddy behind the wheel and theirs half out the window, hollering through a storm of dust. The truck sprayed rocks across the bluebells and lupines that grew over the lip of the gully. The front bumper was stove in pretty good and the passenger-side headlight dangled from its socket. When the truck bounced up and down on the dirt road, its light flashed on and off, as if with sudden sight.

The moose’s head hung over the side of the truck. It rolled in ways that heads are not supposed to roll. His legs stuck out the back, spindly and gray-brown like burnt matchsticks. His antlers banged against the side of truck and the chain-slack danced in the grooves of the flatbed. The sun bounced off the cracked windshield and threw dusty light all over.

They pulled the truck into Billy’s driveway and it died with a convulsive groan. Our daddy climbed down with a whooooooeeeee to the whole world. He walked around the bed, admiring the dead bull. Across the sea of the lawn they were gigantic, my daddy and the moose, the moose and my daddy. All shoulders and antlers, muscle and bone. The sun lit them up something special, and within its wide avenue they were distant and gold.

The girls’ daddy pulled a cooler out from the tangle of legs in the truck, and cracked two beers open on the tailgate. He took a deep drink off one, the kind where you really throw your head back, and handed the other to our daddy. He called out, “Baby girls, we had an accident!”

And we went running over those easy hills whose long grass held heat and ticks and a good deal of our youth spent running. Up close, the truck had blood and fur on the dented parts, and the windshield was a web of fine fractures, its center about the size of a fist right above the steering wheel. Up close, our daddy had a same-sized welt shimmering from his brow.

Our daddies talked above us in the dreamy way of shocked or satisfied men.

“You think the hoist’ll hold him?” Billy’s daddy asked.

“Arm’s too short. Plus I got an engine up. We could pull him out, but then all we got is a moose in the dirt.”

“Reckon it’ll be harder now.”

“Ayuh.”

Previous to that very moment, the only moose we’d ever seen were alive and giant, even at great distances. We knew them to be ornery—lacking all the demureness of deer.

The commas of his nostrils swirled above his upper lip, and his cracked brown teeth were worn flat and stained dirty green. His tongue made spongy marks on the truck’s paint. He had an equestrian face—a Roman nose I guess you’d say—and even though his eyes were set more to the side of his head than straight on, he appeared distinguished. His antlers spread unbelievably, winter boughs in August.

The little ones climbed over each other and into the back of the truck. I unthreaded Billy’s back. When the brace cracked open, her chin peeled away from her chin-rest and she returned to her natural form, the way trees do after the wind comes. We left her brace in the dirt, and Billy’s daddy lifted us into the truck bed. Then, he made for the spigot on the side of the house to wash himself off.

The moose seemed to rise and fall, even dead. Perhaps it was his retinue of flies, so fat they barely flew, the mosquitoes and gnats. Perhaps it was the deer ticks. There were the ticks you could see and the ticks you could only feel, the ones burrowed deep in the moose’s coat. They were hard and blood-fat and everywhere. We climbed in and out of his recesses, quiet but for the small sounds.

Our daddy laid his arm against the side of the truck and watched us kick up dust off the dead moose. He closed his eyes and something in him sagged. The small bits of glass in his forehead caught the light and sparked.

With his eyes still closed our daddy said, “One second he wasn’t there, and the next he was. …”

Billy’s daddy shot the moose after our daddy couldn’t do it.

The moose’s fur was coarse. I pet his neck in the direction of the hole that ran to his heart that no longer knocked around.

I could see him in the woods, his antlers steep-sided and deep enough to hold water. Or the noise of the whole world, if the world’s noise was what they held, and not breezes and undulant storms; the rain on a million million leaves; the final sharp crack.

My daddy opened his eyes “Well,” he said, “I suppose the odds of something terrible happening are a hundred percent.”

I watched the little ones picking at ticks to distraction, while I tried to make sense of what felt like some real important information. But Billy—Billy stood, struck straight with understanding. She looked at my daddy with terrible clarity and picked between the rifles and moose’s long legs, the binoculars and brass bullets, and in a moment so graceful you’d never believe it to be Billy, she bowed and embraced our troubled daddy.

“Come here.” She said, “There’s no real use in blaming.”

C’m hea-uh, was how she said it. Her chin pointed at the place where the trees meet the sky.

Our daddy always referred to Billy—named after her own daddy—as a real stand-up guy. No slouch. That was his big joke. He let Billy hold him longer than anyone generally held our daddy, then he lifted her out of the truck and placed her on the ground, mindful of the soft S of her spine. After a moment, and with a thoughtfulness generally reserved for late nights at the VFW, where the men drank whiskey and talked of god, he said, “Not a one of us gets to stick around. It ain’t personal.”

We stood in the clearing the yard made and the evening slipped down around us, promising the kind of night where the stars really throb and glow. Billy struggled back into her brace, and it took me till dark to twist her up good again. But it was alright, we were done playing. The creeping coolness that turned the lilac from purple to brown would be the same to send us inside soon enough.

(7/23/24)

Nicole Treska is the author of the debut memoir Wonderland. Her short fiction has appeared in New York Tyrant magazine, Epiphany literary journal, and Egress: New Openings in Literary Art. Her interviews and reviews are up at Electric Literature, Guernica, The Millions, BOMB, The Rumpus, and then some. She lives in Harlem with her husband, James, and their three-legged dog, Nadine.