SUNSET IN THE LUNGING RING by Clarke e. Andros

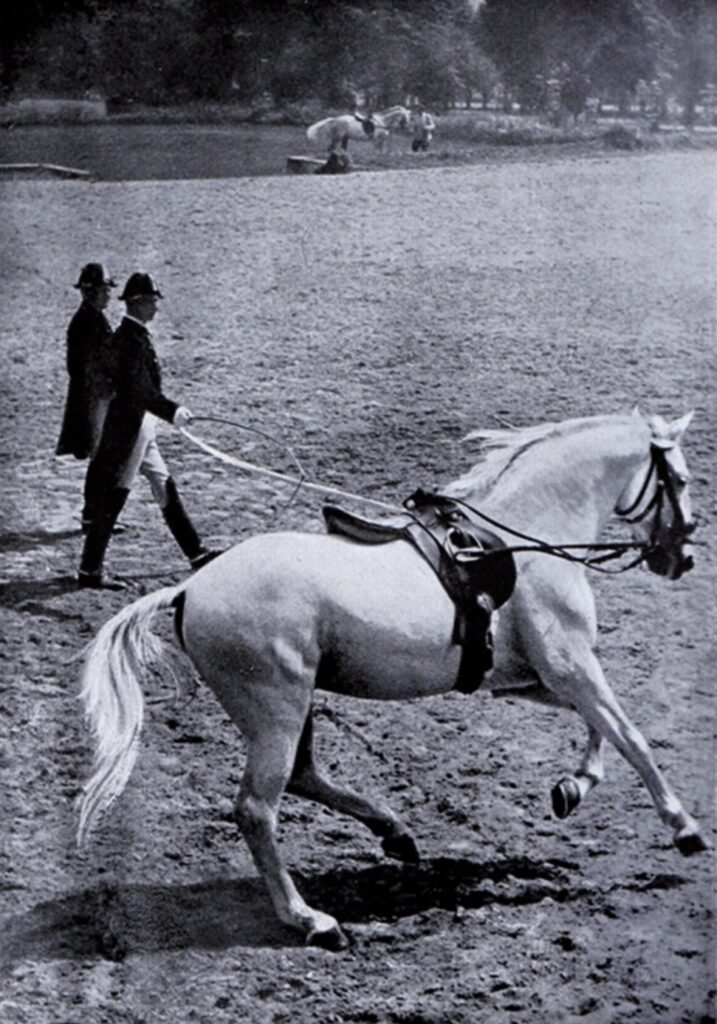

Between Joseph’s home and mine was a vacant field. In the vacant field was a ring. The grass dead and dust, done so under the appaloosa hooves of the neighbors horse. She passed afternoons lunging the horse after her shift delivering Hostess Cakes to liquor stores and market aisles. She did not whip but touched the shaking muscle of the horse’s side above the nobby hocks of its moving legs. The sweat catching bits of sun, the bits that in low angle painted the horse in purples, pinks, and soft gray, a lovers gray, not some Sunday afternoon dull. The horse formed a ring, he ran it endlessly, he trod the ring deeper with each pass.

But that’s not when I walked to Joseph’s house. I walked in the morning. My saxophone, my regret, my burden, clanking against my knee. When I asked to join the band in fourth grade my mother said, if you’re going to do this, you have to see it through. Eighth grade was an abstraction to me then, so I signed in blood I didn’t know was in me. I signed the next four years of morning commutes off for the price of sucking on reeds and lying on practice sheets humming along through the brass tubing to John Phillips Souza. I was terrible but talent or no talent I lugged the black case along every morning of pre-pubescence. An accessory. Walking to Joseph’s when the dew still clung on the thistle, wetting the bottom cuffs of my Levis, soaking through my Vans, touching the top of the socks within.

We started a study. A book given to us by the youth pastor in the next town up. His name was maybe Rick, his name is lost, I am only guessing. The girls in the youth group had a talent for making my breath press the back of my throat, it felt like control, the way their shampoo would smell, only if you ever got close enough to know. The way I could follow their voices like a siren song, panting, trolling, like some starving slumdog looking for scraps. They did not read the book because the book was for boys. One day out of the week we read a chapter before school, on a Wednesday, maybe Thursday, like the pastor’s name, who cares. We read in hushed voices laying on our stomachs in his shag carpet room. The door closed to his family. His father an unbeliever, the tension of which I felt in the popcorn ceiling. We attended church twice a week. My father was quiet too, but he came on Sunday, no guesswork, but Joseph’s father gardened instead and the action of that left me worried. Did he plant mustard seeds? Could he ever? Would he know it if he saw one?

Is there a day we never see our fathers again?

The book told us how to be men. Biblical men. Men that the bible tells you to be, though instead of reading the bible, we read the book, it had illustrations, citations, it was written in an approachable tone. Work ethic, tithing, pulling the chair out, shaving, finding a wife, tying a tie. It was the rules to a game, who knew? The pastor that gave it to us was enormous. A college linebacker and Minnesotan, aren’t they all? His neck was wide, he wore a goatee that transitioned from chin to neck with no seam, all one. The things you remember in place of a name. I don’t know if he learned how to be a man from the same book, though I doubt it. He pulled them off of his shelf like handing tissues to someone contracting with a sneeze. Learning how to be a man is passed along by handing the book from one person to another. A man gave it to us, a man that was not our father, we never spoke to our fathers about the book, we never spoke to our fathers about these things, that’s how it works, that’s the game.

As with all materials dealing with young men, masturbation was tabled. It was in the chapter immediately following how to tie a half-windsor, how to shake a hand, how to pass a knife from one friend to another without anyone getting hurt. The bible didn’t cover it in explicit language so the book needed to fill in the gaps, somewhere on the glossed pages with pops of color. These two things were true. Onan spilled his seed on the ground in Genesis 38 and was struck dead, death by pull out method, Tamar must have wondered what she had. Second, thinking of girls, women, anyone with a body not your own and most likely your own included was lust, a sin, a threat, some abstract violence only known between you and God, that quiet hurt. That was the logic, enough to come to the conclusion that unless you could jerk off to a sunset there was no biblical allowance for the act.

So I jerked off to sunsets. The way they curled out from the horizon and could paint even harsh landscapes into soft skin. The burst of sun, disappearing, floating away, grazing, teasing the edge of the globe before that final plunge over the side of the earth. This was an age of magnetic pull, my body begging for touch.

Sometimes though the landscape would slip, to bra strap, hot breath, kind laugh, to thoughts of some girl in the youth group audience listening to the pastor with the thick neck. Lessons about how to be. Lessons on how to live in a world of setting suns. At those times I would try to steel myself. Hold off for gradients, cumulus topped plateaus, celestial movement, days end. I would whip my back in words. Whip myself into a denial of mind. Until I ejaculated into my hands at dusk, the world sliding to darkness.

In the after. In that shame glow. I would think about the horse in the ring. In the vacant field between my house and Joseph’s. Between homes paid for by quiet men. The way the horse ran itself into sweating sides, lather building between hind legs. The way the neighbor, the way she pushed it along, a tender graze of the whip, pushing it to circle. The way it moved in changing light. The way it kept running. The way I could hear it in the new night dark. Running.

(9/9/23)

Clarke e. Andros is a writer from California.